Phase Velocity and Group Velocity

Superposition of Light Waves

When we analyze the resultant of two or more simple harmonic vibrations (monochrome light waves), we usually can treat it as the simple sum of the individual vibrations (waves) as shown below.

Note:

This linear treatment is only true for low power intensity lights. When the power intensities are very high (such as with an electric field strength at 1012 volts/meter), non-linear effects will be excited and the simple sum method should not be used.

However, in this discussion, we can use the simple sum method.

Superposed Wave of Different Frequencies (very small difference) and Beats

We will now discuss the superposition of two waves that have same vibration direction, same amplitude a, but different frequency and wave number(ω1, k1, ω2, k2). However, the frequency difference is very small. This will generate the very interesting “beat” phenomenon.

Since the phase difference between the vibrations is continually changing, the specification of some initial nonzero phase difference is in general not of major significance in this case.

So we can suppose that the individual vibrations have an initial phase of 0, and hence can be written as:

Then the sum of these two waves is:

Using the following triangular formula

We get

We then introduce the notation of average angular frequency![]() and average wave number

and average wave number![]()

And modulation frequency ωm and modulation wave number km

We then get

We can make

Then we get

This means that the resultant superposed wave has an angular frequency , and its amplitude varies between 0 and 2a with time t and position z.

, and its amplitude varies between 0 and 2a with time t and position z.

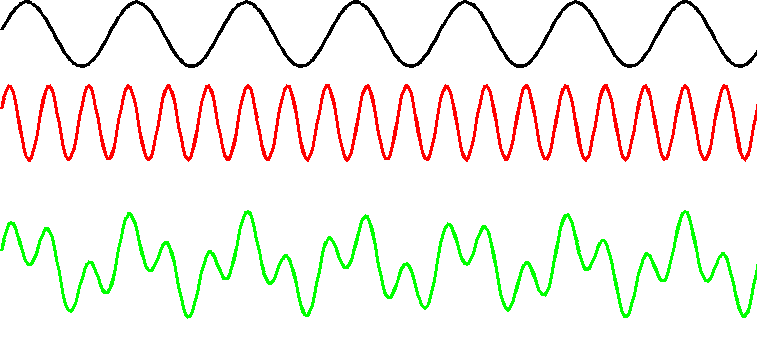

The following picture shows the superposition result. Since light waves have very high frequency, if ω1 ≈ ω2, then  >> ωm, which means that A varies slowly but E varies extremely fast.

>> ωm, which means that A varies slowly but E varies extremely fast.

Intensity I of the superposed wave is proportional to A2, we have

or

So intensity I varies between 0 and 4a2 with time t and position z. This phenomenon is called “beat”. From the last formula we can see that the beat frequency is 2 times of modulation frequency ωm, from ωm’s definition ωm =(ω1 - ω2)/2, we can see that the beat frequency equals to ω1 - ω2.

This process, as a purely mathematical result, can be carried out for any values of ω1 and ω2. But its description as a “beat” phenomenon is physically meaningful only if |ω1 - ω2| << ω1 + ω2.

Phase Velocity and Group Velocity

Clearly the velocity of a monochrome light equals its equiphase surface propagation velocity. However, in the case of a superposed wave, we need to carefully define its propagation velocity.

Let’s continue using the superposed wave equation from above:

The superposed wave has two propagation velocities: equiphase surface propagation velocity (called Phase Velocity Vp), and equiamplitude surface propagation velocity (called Group Velocity Vg as defined by Rayleigh).

Phase Velocity of the Superposed Wave:

Phase velocity Vp can be concluded by keeping the phase a constant:

Then by doing derivative of z we get the Phase Velocity Vp of the superposed wave:

Group Velocity of the Superposed Wave:

Similarly we can get the Group Velocity Vg by keeping the amplitude a constant:

Following the same steps, we get the Group Velocity of the superposed wave:

when Δω is very small, we then get:

So Vg is the partial derivative of ω.

Relationship between group velocity Vg and phase velocity Vp

Based on the definition Vp = ω/k, we can replace ω with k*Vp, then we get

Since

and

then we get

Dispersion

When these two monochrome waves are propagating in vacuum, they have the same phase velocity c (the speed of light in vacuum), and the superposed wave’s phase velocity equals its group velocity(both are c).

However, when these two monochrome waves are propagating in a dispersive medium, they will have different velocities and thus the superposed wave will have a phase velocity Vp that is different from its group velocity Vg.

(Note: Dispersive means that in this medium different wavelength lights have different phase velocities)

So that means the bigger dVp/dλ, the bigger the difference of velocities for different wavelengths, and the bigger the difference between the superposed wave’s Vp and Vg.

Normal Dispersion

If in the dispersive medium, dVp/dλ > 0, then longer wavelength lights propagate faster than shorter wavelength lights, this is called normal dispersion.

In this case, the superposed wave’s group velocity Vg is smaller than its phase velocity Vp, and in some cases, the group velocity can even be negative (travels backward)!

This is best shown with the following video.

Anomalous Dispersion

And on the other hand, if dVp/dλ < 0, then longer wavelength lights propagate slower than shorter wavelength lights, this is called anomalous dispersion.

In this case, the superposed wave’s group veloicty Vg is larger than its phase velocity Vp. Again, this is best shown in the following animation.

Zero Phase Velocity

When the monochrome waves are propagating in opposite directions, they can make the phase velocity Vp of the superposed wave to be 0.

Zero Group Velocity

You can also make the superposed wave’s group velocity Vg to be 0.